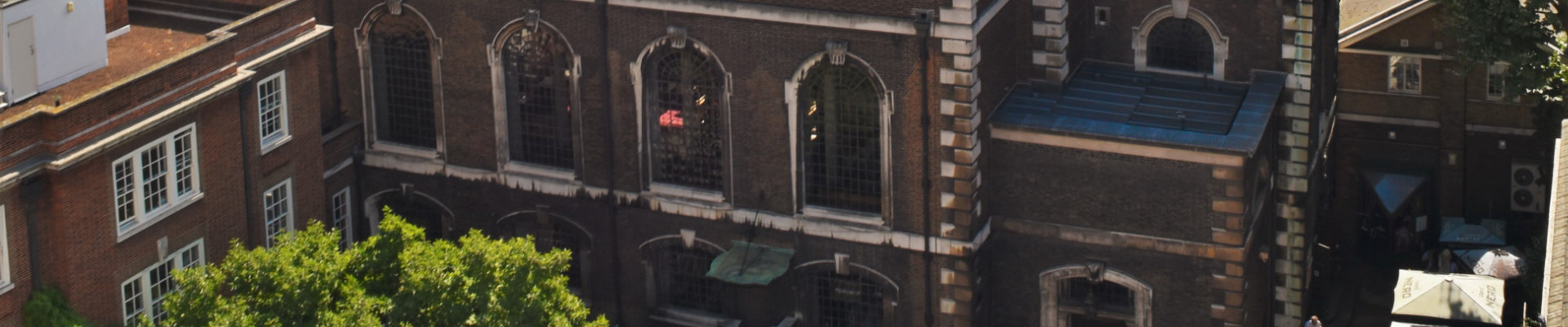

ASWA Annual Service at St James’s Church, Piccadilly, 6th October 2019

Revd Jeremy Fletcher

Ask the animals and they will teach you

Job 12. 7 -13

Luke 12. 16 – 32

ASWA at St James Piccadilly, 6.10.19

I am here because of a donkey. There’s much more to it than that, of course, but the donkey was pivotal. Cathedral Precentors get to help shape all sorts of acts of worship, but when the Anglican Society for the Welfare of Animals came calling at York Minster in 2005 to prepare for its annual national service it was the donkey which provided our focus. Pets would be welcome and animals would be blessed if they came, but this was about animal welfare, and the presence of a donkey would focus our thoughts and our prayers. It focussed the minds of the vergers too, because they were the one with the buckets and brushes.

Donkeys are a barometer the world over for the way animals and humans relate. There almost needed to be no formal prayer at the point the donkey came down the aisle. My photograph of the event includes the Lord Mayor of York in close proximity. She had entertained the Queen not that long before. I hope that Councillor Greenwood was even more connected to the depth and wonder of creation in the service than she was when she rode in a carriage with the Royal Family down York Racecourse. What was I taught, and what did I learn when a donkey came down the aisle, and looked at me and looked at us? Specifically the donkey caused me to sign up to ASWA, and thankfully I’ve just paid this year’s subs…

“Ask the animals and they will teach you”, says Job to Zophar the Naamathite. In telling Job the correct way to think about the divine purpose, Zophar, with youthful arrogance, has compared Job to an “empty headed donkey”. “Since you mention animals…” says Job, “What do they know? With what are their heads full?” They know that “the hand of the Lord has done this”, that in hand of God “is the life of every living thing.” This is no sentimental anthropomorphism, attributing human emotion and thought say to the expression of my cat when she wants feeding. What Job says springs from a humble and awed attention to the complexity and variety and detail and majesty of the created order. Give regard to animals and fish and plants, says Job. You’ll learn. God makes. God sustains. They know that.

Two poems have flown into my life recently. As a recent London resident I do love the “Poems on the Underground” project. Did you see The Meaning of Existence by the Australian poet Les Murray this summer?

Everything except language

knows the meaning of existence.

Trees, planets, rivers, time

know nothing else. They express it

moment by moment as the universe.

Even this fool of a body

lives it in part, and would

have full dignity within it

but for the ignorant freedom

of my talking mind.

Les Murray, from

Poems the Size of Photographs, 2002

The universe knows.

The other poem is by Neil Curry and is called A Benedicite. It’s full of animal facts. You can tell the temperature by using a Snowy Tree Cricket. All you have to do is count the number of chirps in a 15 second period, add 40, and that’s the temperature in Fahrenheit. It’s called Dolbear’s Law, and has been around since 1897. Amos Dolbear gets the glory, but it was Margrette Brooks who first recorded the observations a decade before. It’s not the first time a man has got the credit for work first done by a woman, but that’s another sermon. Anyway, Neil Curry begins his poem with a quotation summing up Darwinianism, and then gives us things to make us gasp about what animals can do.

A Benedicite

‘through the mechanistic operation

of inanimate forces and by the power

of natural selection’

we have:

the cuttlefish, which expands

and contracts bags of yellow, brown,

orange and red pigments embedded in its skin

so as to change colour and blend

in with its background;

and the eye of the common newt,

whose lends, when removed surgically,

will grow again

from the edge of the iris;

and the bombardier beetle,

which defends itself

by squirting out a jet

of noxious benzoquinones

at a temperature of

100 degrees centigrade;

and the male emperor moth

which can detect a female

emperor moth by her smell

at a distance of

eleven kilometres, up wind;

and that series of small peristaltic pumps

arranged along the oesophagus of the giraffe

which enable it to lift water

up to the required height of three metres

when it is standing, head-down

and legs-straddled, drinking;

and the in-built thermometer

of the Snowy Tree Cricket:

add 40 to the number of chirps

it emits in any period of 15 seconds

and you have the exact air temperature

in degrees Fahrenheit.

For these, and so much more,

O, ‘Mechanistic Operation’,

we give thee thanks.

Neil Curry

From Walking to Santiago Enitharmon Press 1992

You called me a donkey, says Job. Have you ever wondered what the donkey knows, and can teach you? Have you ever wondered what the bird knows, and will tell you? These are things of such wonder that you should really be stunned into silence, and awed into shame, especially when you consider what use you make of these creatures, what abuse you heap upon them, what misuse you put them to by devastating their habitat and turning them solely into single use industrial providers of nourishment for an overweight and indulgent humanity. Above all, says Job, a donkey is not empty headed. Its head is full. It hears what you are deaf to. It sees what you are blind to.

At the very end of the book Job himself is stunned into deeper silence when God unfolds this all the more. It is the poetry, like the poetry of Psalm 104, like the teaching of the lilies of the field and the birds of the air in Luke 12, like the original Benedicite to which Neil Curry’s poem pays homage, the text from the Apocrypha which is one of the glories of the church’s worship, and such a feature of medieval church art and architecture, wonderfully depicted in the South Transept roof of York Minster, and remade after the fire so that twenty years later an ASWA donkey could stand under it and teach us. Pay attention to the whole of creation and you will be cured of the temptation of thinking that you know, and can rule, and can build barns big enough to make you stop relying on God.

Jesus’s public ministry, revealed in his baptism, is honed by his experience of temptation in the wilderness. There is a brilliant verse in Mark’s brief telling. After the temptations, Jesus was “with the wild beasts, and the angels waited on him”. Translators I trust put it this way: “wild animals were his companions”. It may well be because of ASWA, but I now include dogs in our service registers at Hampstead. I am deeply jealous of those churches which have a resident cat, and feel no visit to Southwark Cathedral is complete without seeing Doorkins Magnificat.

Today is about so much more than recognising animals as companions and teachers. It is about being humbled, broadened, awed, and challenged. Today is about a theology of creation which sees Christ in all and through all, a theology which makes us question how we are with animals, what we are doing to them and for them which is contrary to the way creation can be and should be, what our effect on this planet might be if we cherished more and exploited less. That will lead some of you to remove yourself from anything which is produced by or from animals. It will lead all of us, I hope, to ensure that their welfare and their habitat is all it can be. It may lead some of you to occupy a faith bridge tomorrow, and to protest with all you have about the environment. It will lead all of us, I hope, to address every possible behaviour which harms and to do everything possible that will sustain.

This is not about human self interest, or just about making sure our grandchildren have a place to thrive. The incarnate Lord had wild beasts as companions. Job invites us to know what they know. When we recognise ourselves as fellow creatures, and know that we, with them, are fearfully and wonderfully made, then we will tread more lightly and more confidently, serving them and each other as companions of Christ, and so making Christ known, until that day when the whole creation will rejoice with the glorious freedom of the children of God, to whom be all praise, now and for ever. Amen.